What I Learned About Writing From… Hereditary.

My love for horror began with film. It wasn’t until I was a teen and I got my hands on my first Stephen King novel (Pet Semetary) that I even realized horror novels were a thing. Of course, as an adult, my love for horror hasn’t waned, but now that I’m a writer, I examine films a bit more critically than ‘that was awesome’ and ‘that sucked.’

So, I decided to start a blog series dissecting what I learned about writing from my favorite horror flicks. Starting with one of my top modern releases, Ari Aster’s HEREDITARY. Spoilers entail. If you haven’t watched the film, do yourself a favor and go watch it, then come back to this post.

Opening Images:

The opening image in a film is like the first line of a novel (or the opening paragraph). Filmmakers and authors can use this moment to achieve a number of things: Set the tone, introduce a theme, establish setting, plunge us into a character and their voice. It’s a matter of taste.

Masters like Ari Aster do it all at once.

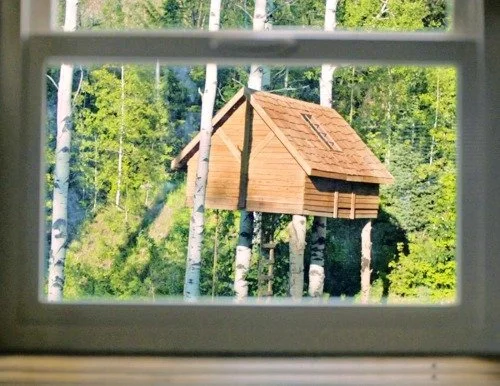

The opening image in Hereditary establishes the setting by panning from a shot out a window at a treehouse into a workspace and a bunch of dioramas. The shot zooms in on a bedroom of one diorama until we notice a teenage boy, Peter, asleep in his bed. Altogether, these things are very much horror genre conventions. We have an eerie house and we can immediately assume that a lot of horror conventions that take place within the home are fair game. We get a dose of the theme, that this family is a group of characters in a larger play dictated by forces they aren’t aware of, pawns if you will. But most importantly and, most subtly, we open with the central character. The thing is, the viewer doesn’t realize Peter is the central character until the end. So much of the movie focuses on his mother, Annie, and her grief. It isn’t until the end that we realize that the entire plot of the film has revolved around Peter and the antagonists’ objectives for him.

What can this tell us about writing? The best novel openings exert a mastery over all of these things as well. Readers are sprung into the genre, the themes, the setting and the central character. The first opening line that comes to mind is the first line of Donna Tartt’s prologue in THE SECRET HISTORY (will say as much as I can without spoiling this one for anyone who hasn’t yet read):

“The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.”

Immediately, Tartt delivers the reader genre expectations (someone is dead, who is Bunny and how did they die?). The third line tells us this is happening in Vermont. This is a story about a group of people, people who might be naive and have learning to do, which sets the novel up for its themes around enlightenment.

When Breaking Genre Conventions Works:

In horror, there are several ‘beats’ that are essentially mandatory to the genre. The ‘attack of the monster,’ ‘in the monster’s lair,’ and ‘at the monster’s mercy.’ The thing is, on first watch HEREDITARY doesn’t necessarily feel like a horror film at all, but a family melodrama instead. It doesn’t seem to feature a monster and the only thing the family seems to be surviving is grief and tragedy. On first watch, Ari Aster skips over the standard genre beats. There’s no ‘attack of the monster’ as an inciting incident. There’s no investigation leading the protagonist into the monster’s lair. There doesn’t seem to be any monster at all for the majority of the film. All of that changes, though, when Annie discovers the truth about Joan and her mother. Suddenly, viewers realize that the family has been at the mercy of the antagonistic force all along and it puts every other moment of the story into perspective.

That said, on second watch, HEREDITARY does in fact follow genre conventions. The inciting incident and the initial ‘attack of the monster’ beat is fulfilled when Charlie is tragically decapitated. Ari Aster hints at this by breaking up the party scene leading into that horrific moment with a shot of Annie’s diorama and a miniature version of her dead mother in a nightgown, standing in the doorway watching as Annie’s miniature self sleeps.

On second watch, Annie does go into the monster’s lair when she visits Joan and, to top it off, while she’s there she makes herself incredibly vulnerable. She confesses things to Joan that viewers assume she hasn’t confessed to anyone outside of her family, things that are disturbing to the viewer such as she may have tried to kill her children (because was she really sleepwalking?).

What can this tell us about writing? Genre conventions and beats matter. HEREDITARY works so well because it appears to break conventions, without breaking those conventions. I argue, Aster knew exactly what he was doing. The shot of the diorama in the middle of the party scene, Annie’s vulnerability during her confession in Joan’s apartment, the bit of sediment Annie finds on her tongue while drinking Joan’s tea, all of these things demonstrate that Aster was aware these horror beats would appear to be missing on first watch and so he instilled moments that injected the mood of those beats back into the scenes. In order to subvert expectations, you have to understand why those expectations exist. As frightening as HEREDITARY was the first time around, it’s all the more horrifying when you rewatch it and these beats all the more delicious.

The Art of the Scene:

Aster masterfully crafts scenes in HEREDITARY. They’re all nuanced and layered and offer new meaning with each watch. One of my favorite scenes is Annie’s visit with a grief group after her mother’s funeral. She delivers a long, brilliant monologue. On first watch, the scene appears to be about her, her struggle with her emotions, and her complicated relationship with her mother. The monologue’s exploration of her emotions and her family’s past is so well crafted, the scene is totally gripping even if it only serves that purpose.

On second watch, though, viewers realize the scene is loaded with foreshadowing and vital backstory. Annie’s father starved himself to death. Her brother killed himself and claimed their mother was ‘trying to put people inside of him.’ On second watch, viewers realize her mother has tried to do this before, that this antagonistic plot has been foiled in the past.

Could Annie have foiled the cult’s plan if only she realized sooner? Could a simple accident (such as Steve running a red light and getting t-boned after he picked Peter up from school) have changed their fates? Was it really fate in the end? Clearly, the cult and Paimon aren’t unbeatable, they’ve been beaten before. By including this backstory and foreshadowing, Aster interrogates his own themes. Ultimately, then, the scene serves three functions: Exploring character emotion, using backstory to foreshadow, and interrogating the film’s themes.

What can this tell us about writing? Quite simply, writers can make their scenes do more and writers need to challenge themselves to do so. Take a scene you’ve already written and ask yourself, ‘what is its central function?’ Then, ask yourself what other functions it can serve. Push yourself to dive deeper, to come up with at least two additional functions, and try reworking the scene with these in mind.

That’s it for now! Let me know what you think and if there’s anything you learned about writing from Hereditary.