Crafting Suspense

At the beginning of this month, I took a virtual seminar with Rob Hart, author of works such as The Warehouse and most recently Paradox Hotel (both of which I highly recommend). The course was offered through Writing Workshops. Hart has some great things to say about writing, process, and publishing so if you get a chance to take a workshop with him, I highly recommend doing so. One of the things I’ve been reflecting on was an article Hart shared.

The article, penned by Lee Childs, is about creating suspense. I highly recommend reading the entire article here. A quick excerpt:

"How do you create suspense?" has the same interrogatory shape as "How do you bake a cake?" The right structure and the right question is: "How do you make your family hungry?"

And the answer is: You make them wait four hours for dinner.

After reading this article, I found myself thinking over stories with elements of suspense that struck me. I wanted to take a deep dive into examining the function of dramatic questions and suspense in order to better absorb the rich lessons Childs offers in less than three pages.

In order to better dissect these elements, there will be spoilers for each book. The sections will be headed with the title, author, and image so you can easily scroll without catching spoilers. I highly recommend scrolling to those you have read because there’s plenty of unpacking done here. I’ll be taking a look at Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, The House We Grew Up In by Lisa Jewell, Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, and Dark Matter by Blake Crouch. You can also scroll to the bottom for final key takeaways sans spoilers.

First Up:

Rebecca

by Daphne du Maurier

In Rebecca, an unnamed protagonist marries widower Maxim de Winter after a whirlwind romance in Monte Carlo (I should say, she is unnamed until she becomes Mrs. de Winter). Upon returning to his home at Manderley, she discovers that his dead wife, Rebecca, haunts her marriage.

Daphne du Maurier first injects the dramatic question of what happened to Rebecca at the tail end of the fourth chapter, when the trite Mrs. Van Hopper informs the protagonist that Rebecca’s death was a tragedy, that she was drowned and that “they say [Maxim] never talks about it, never mentions her name.” Naturally, readers mistrust the face value of his silence and intentionally so. Had du Maurier presented this initial information through Maxim, the reader might perceive him differently—as a widower meant to be sympathized. Instead, the reader is positioned to mistrust him. When the protagonist goes to Manderley with the husband she hardly knows, the reader is not only wondering what really happened to Rebecca, but if the protagonist might have married a murderer and, worst of all, if he might murder her as well.

But what I love the most about Rebecca is the way du Maurier experiments with the shape of suspense. Instead of making the circumstances of Rebecca’s death the pinnacle dramatic question, the story takes a sharp turn at about ¾ of the way through when the dramatic truth is revealed: Maxim did kill Rebecca and her body has been discovered. Du Maurier spent so much of the novel positioning Rebecca as an invisible antagonist creating conflict and tension in the life of our unnamed MC, that the reader happily takes for granted that Maxim’s story about how and why he killed her is true. Thus, the final question that fuels the reader through the end is not, Did he kill Rebecca? But rather, Will he get away with it?

The tension peaks with the protagonist’s marriage crumpling under the weight of the initial dramatic question and the truths Maxim is withholding from her. Then, we’re allowed a fleeting breath of relief as they reconcile over the sharing of Maxim’s secrets. Moments later, however, the phone rings and we’re spun into the second dramatic question which propels the reader to an even higher level of tension—at any moment, Maxim could be thrown in prison and the protagonist’s new world will come falling down around her.

The House We Grew Up In

by Lisa Jewell

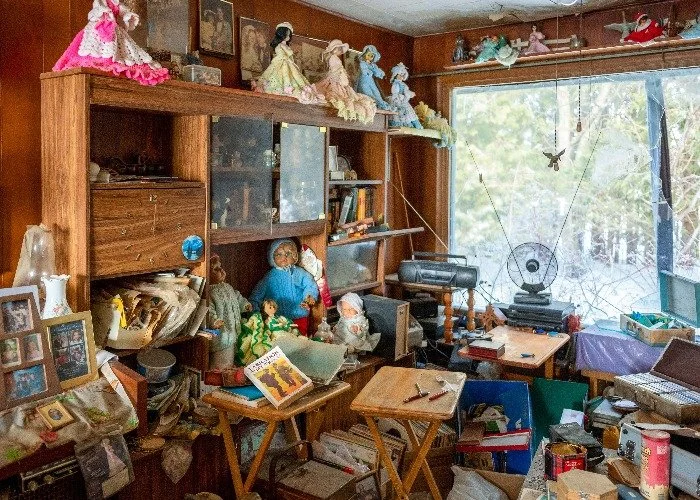

The House We Grew Up In is a dual timeline, multi-POV family saga centered around the Bird family whose matriarch, Lorelei, suffers from a hoarding disorder. In the present timeline, Lorelei has recently passed away and the eldest daughter, Megan, is left to deal with their mother's home. The past timeline navigates the family's history, a tragedy that irrevocably changes them, and the secrets that drive them apart.

It’s Jewell’s work with multi-POV that really shines here. It’s a masterclass in how to craft suspense through dual timelines and multi-POV. It’s the juxtaposition between the family’s then and now that poses the dramatic questions: What happened to this family? How did this once close knit family fall apart? Then more specifically, about 10% of the way through, the reader is positioned to ask what happened between Megan and her younger sister Bethan. In the flashbacks, they’re inseparable, but in the present Megan hangs up on Bethan as soon as she hears her voice on the other end of the line. Why?

About 25% of the way in, we get the first flashback from Bethan’s POV where the seed of the answer is planted: Bethan harbored a crush on Megan’s husband, Bill, and we get a hint that he might have returned those feelings. But Jewell doesn’t walk us through the development of their affair, because the focal point of the novel’s suspense isn’t whether Bethan will or won’t sleep with her sister’s husband. In Bethan’s first scene, she has a crush on Bill and, thirty pages later, they are mid-affair.

The question Jewell poses isn’t, Will Bethan sleep with Bill? Or even, Will Megan find out? But rather, How will Megan find out? By interweaving between present and past, first letting us know that these once inseparable sisters no longer speak, the reader knows the secret is eventually revealed. The suspense of waiting for that dramatic revelation is like waiting for a bomb to go off and Jewell draws it out for 200 pages.

Granted, Jewell did an incredible job plotting each family member’s storyline so that in those 200 pages there is plenty of character development and fresh drama that interweave into this main secret. There are scenes where Jewell teases the reader with the secret, such as when Megan and Bill go on vacation and she sees Bethan calling him. The Home We Grew Up In is one of those books that is quite literally unputdownable and all because Jewell let the reader in on this little secret. Sometimes posing questions isn’t about withholding information, but about giving just enough of the right information.

Never Let Me Go

by Kazuo Ishiguro

Never Let Me Go is a fantastic example of the suspense that can be crafted out of worldbuilding. In the opening scene we meet our protagonist Kathy, her best friend Ruth, and a temperamental boy named Tommy. We also get allusions to ‘carers’ and ‘donors’ and the mysterious donations they make, as well as an introduction to a strange boarding school. Because Ishiguro peppers these worldbuilding elements without any explanation, the novel is fueled by many questions—who are these donors and what are these donations? What is Hailsham and why are the students there? Outside of these questions, the novel is a coming-of-age story filled to the brim with teenage drama—love triangles, bullying, and sexual confusion abound. But the questions remain unanswered and the suspense that creates casts a shadow of tension over the otherwise trivial lives of the novel’s characters.

Ishiguro reveals slivers throughout. We get hints in the first third of the book that their lives are limited, that they don’t have options such as regular children do, that these aren’t regular children at all. When the reader finally understands that these seemingly simplistic and shallow characters are clones created for organ harvesting, Ishiguro weaves a final question in: Can our protagonist and her love interest buy more time? So much of their lives had been wasted on tedious (frankly) bullshit, that the answer to this question is all the more important.

Ultimately, this novel reminded me of Hitchcock’s classic suspense metaphor: A couple is sitting in a restaurant, unaware that a bomb is strapped beneath their table. They chat away and every second spent on small talk is a second lost to escape or somehow prevent their fates.

What impressed me most is how this strategic weaving of suspense through worldbuilding allowed Ishiguro to break a number of writing rules. Characters were constantly relaying conversations, nearly every scene transition was handled rather haphazardly, there was a heavy reliance on showing, the characters never had any clear goals until the very end of the novel, and yet it was gripping simply because Ishiguro withheld the right information and made the reader hungry to understand Kathy’s world.

Dark Matter

by Blake Crouch

As a final examination, I wanted to look at one of my all-time favorite books, Dark Matter. One of the things that impressed me upon re-reading is the way Crouch crafts suspense at a micro-level, sentence to sentence. We get this from the very first page when Crouch serves the reader a spoonful of dramatic foreshadowing. He interrupts a seemingly mundane moment depicting protagonist Jason’s Thursday night with, “I’m unaware that tonight is the end of all of this. The end of everything I know, everything I love.”

The foreshadowing is on-the-nose, yes, but it immediately challenges the reader to guess at what’s about to happen. Ten pages later, the foreshadowing is recalled: “Without thinking, I step into the street against a crosswalk signal and instantly register the sound of tires locking up, of rubber squealing across pavement.”

The narrow miss is a tease, reminding the reader some big event is looming in the shadows, waiting to ensnare Jason. But what?

When Jason is kidnapped a few pages later, Crouch continues injecting questions beyond the obvious ‘Who is this person and why are they kidnapping Jason?’ The details of Jason’s home and work addresses in the kidnapper’s GPS clue us in that this isn’t a random encounter, they’ve been following Jason, but how long and what for? Why is the kidnapper’s voice familiar? How do they know each other?

Even Jason’s attempt at getting help is framed within a question. He doesn’t simply send a text message on his phone, but first risks “an experiment,” first taking his hand off the wheel, testing to see if the kidnapper notices so that another question is inferred, Will Jason be able to send a text message for help? Crouch drags out Jason’s clumsy attempt at alerting his wife for nearly two pages before he’s finally thwarted by his kidnapper.

Then, Crouch layers in more questions: How does his kidnapper know intimate details about his life? Who his old roommate was, that Thursday nights are family night, why does he care what Jason’s schedule for tomorrow is? Crouch even has Jason wonder questions for the reader: “Why the hell does he want me naked?” (23) “What if he tries to rape me? Is that what this is all about?” (24) “Does he have plans for Charlie and Daniela?” (26)

Crouch begins character turns with questions. When Jason reflects that he’s following the kidnapper’s instructions so obediently he asks himself, “Does this mean I’m a coward? Is that the final truth I have to face before I die? No. I have to do something.” (29) Positioning the reader to wonder what Jason is going to do to get out of his situation now.

Crouch even ends the chapter on a question, “Now what?” And the answer is so vague (“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you.”), it solves nothing for the reader, creating the perfect cliffhanger to propel the reader forward.

What can writers learn from this?

First, boil down your dramatic question. What is the twist of your novel? What is the final revelation that pulls all of your narrative threads together? If, for example, your novel is a murder mystery, the dramatic question might be about the murderer’s identity. But maybe it’s deeper than that, maybe it’s the murderer’s motive or their connection to the victim. Whatever the ultimate twist is, make sure you find a way to allude to the question early on.

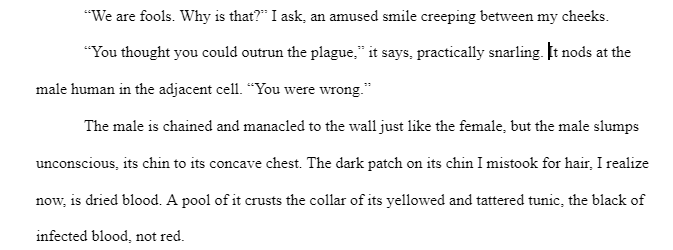

But also, don’t settle there. When you’re editing scenes, find ways to create suspense at a paragraph and line level. Find a scene where some new information is revealed to the protagonist and instead of simply having the protagonist find out, try first creating a question within the scene that is then answered. I won’t pretend to be a master of suspense, but you can check out the results of doing this exercise with my WIP below:

(Before)

(After)

That’s it for now. If you try this scene level exercise, share it on Twitter and tag me!